After work, I walk up the big hill and slip into the side door of a squat brick building. The third doorway reveals a small but surprisingly comprehensive library of donated books; this is the home of Books to Prisoners, a non-profit where I’ve been volunteering once a week. People who are incarcerated write to us with requests, and we browse the shelves in search of titles we think they’d like. Many of the letters are all business: hi, I’d like some books, here’s my name, prison ID, and mailing address. Most ask for the same genres — people love comic books and manga, thrillers and mysteries, fantasy and sci-fi.

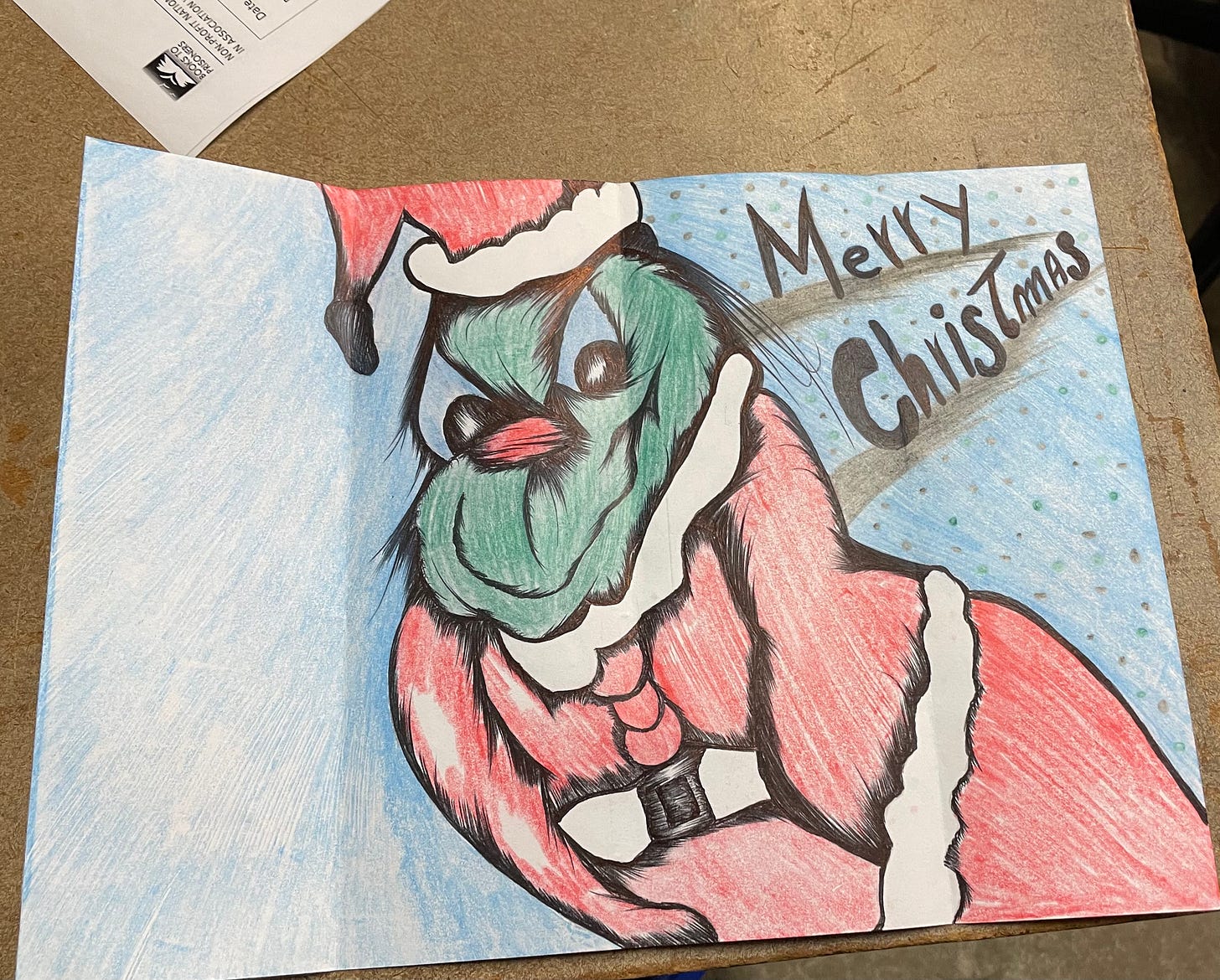

So it’s a real joy to open letters that deviate from that formula. Yesterday, another volunteer opened an envelope to find no letter, but a carefully drawn Grinch in a Santa outfit. I opened one from someone who told me about the wizard costume he was planning for Halloween (complete with a sketch of a wizard, of course), and requested anything on folklore or mythology for a book of fairy tales he was writing. Sometimes, the letters include little glimpses into people’s lives: one asked if we had anything about the Seattle music scene; his son, a musician, was moving to the city soon, and he wanted a way to connect with him. Another asked for books by a specific author that were published in the last six years, because that’s how long he’d been incarcerated.

One of the rules I learned in my training is that we must stick to a fairly dry and impersonal script in our replies to these requests. That’s partly due to a lack of space; there are only three lines on the form where we include details about what we’re enclosing. But that policy is also to ensure our packages are not marked as “personal correspondence” — another class of mail entirely. Some form of “hope you enjoy” is about as personal as we can get.

It makes me deeply uncomfortable to reply to letters, especially heartfelt ones, with minimal acknowledgment of their personhood. Part of the reason I started volunteering at BTP was a strong belief that all people deserve respect and access to information, hard stop (ask anyone I know: my love language is information), but I also believe care and connection go a long way in making people feel like people. When I read about someone’s children, or the classes they’ve taken in prison, or the business they want to start when they get out, it’s hard to write the same rote message: “Hi John! Here’s that James Patterson novel you requested — hope you enjoy!” without acknowledging all the personal things they’ve shared. I want to say hey, that sounds hard, or that’s really cool you’ve gotten interested in astrophysics. And almost always, I grow curious about their story.

One week, that curiosity hit me hard. I was at the end of my shift and decided I’d reply to just one more letter. I picked up an envelope and immediately, it stood out to me: the writer’s blocky handwriting was so tidy, it looked like a font. In his letter, the sender wrote that he enjoyed “strange and obscure” literature — the first missive I’d received requesting a literary novel! I sent him Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and a few other novels, and called it a night.

The next morning, I woke up thinking about that letter. I’d forgotten his name, but ten minutes into my first cup of coffee, it popped into my head wholesale. I took it as a sign: clearly, I should google him!

Googling strangers has never led me to anything I wanted to see, so I don’t know what I expected. No, actually, I do: I thought his neat handwriting and taste in books meant something about him. I wanted to believe he’d been convicted of something minor and unfair, like marijuana possession. Perhaps he was even wrongfully convicted! In reality? He was convicted for possession of child pornography. I don’t know anything else, because I refused to click any of the links to news articles about his case. Illusion shattered, lesson learned: never again will I google a letter writer.

I thought about the children and families that this man hurt. Were people showing them kindness and helping them heal? Should I be spending my time doing that instead — and by extension, was my time misspent helping people who have seriously harmed others? And what does it mean that our carceral system hurts them back — is that really justice? Some people have said in their letters that their prisons have no libraries or that they’re in solitary detention and have only the books we send to keep them company. (I won’t even get into the dehumanizing rules around the types of books we can send.) And I think the people who are harmed by the system as a whole: the prison employees witnessing (and perpetrating) dehumanization every day, the musician son moving to Seattle while his dad is behind bars, and the millions of other families affected by the U.S.’s prison industrial complex.

That brought up even more questions for me about continuing to do this work. Is it fair to judge a person by the worst thing they’ve done? Can people really grow and change? Can the books we’re sending really help people grow and change — or is it more about the act of sending books as acknowledgment of a person’s humanity and right to knowledge?

I don’t believe these questions have clear answers, and something tells me that is the point. Many things can be true at the same time, and letting that discomfort exist is a practice in accepting the world as it is. It’s easy to lob criticism at any volunteer gig; you can always justify doing nothing on the grounds that nothing is perfect. But for me, my weekly trip to BTP is a meditation on what justice means, a practice in showing up imperfectly, an act of hope.

If you’re in the Seattle area and you’re curious about Books to Prisoners, here’s their website.

Lately

People are fond of saying that our brains are “fully mature” at 25. That’s not quite true, but it’s not quite false, either! I trace the origin of this popular factoid in a feature for Slate.

Men’s Health interviewed me about psychedelics and The Microdose.

Seattle friends: I’ll be a panelist at KUOW’s Year In Review on December 15! Come watch us discuss the biggest and weirdest stories of 2022. Tickets are $15 and you can get them here.

Letters of Recommendation

Mike Birbiglia’s podcast Working It Out. (Fellow science journalist Kate Gammon recommended this one.) I’m new to exploring comedy writing as a craft, so I love hearing Birbiglia and guests riffing on new material, and being real about the vulnerability stand-up requires.

The Seattle Times Rant & Rave column. People simply write in to complain or praise something, and entries range from heartwarming to unhinged. Big “old man yells at cloud” energy. My all-time favorite:

RANT to the pizza commercials that go into slow motion when a slice is being taken from the pie. Showing the cheese is a psychological ploy. I never get that with my pizzas as they are cut all the way through and I have to ask for extra cheese. Such commercials are a bit over the top and cheesy.

Sabrina Carpenter’s album Emails I Can’t Send. (Also her website is a delightful throwback, but it makes me feel ancient because I don’t think she was alive when the internet still looked like that?)

Watching all of Laguna Beach in a week. On the upside, these kids’ low-stakes high school drama powered me through 100 miles on the bike trainer. Still processing what I watched — though I will say I’m strongly Team Trey and extremely anti-Jason — and am now working my way through Stephen Colletti and Kristin Cavallari’s show Back to the Beach, where they recap each episode.

Selling me your Taylor Swift tickets! No, seriously, I did not get any so on the off-chance that anyone has an extra, I’m shooting my shot here. In exchange I can offer U.S. currency, eternal gratitude, and a guarantee that I am an extremely fun and enthusiastic friend to go to a show with.

The job interview to become a public defender in Minnesota requires you to explain your personal philosophy on all of these exact issues in detail. Loved hearing yours, not enough people talk about this stuff publicly.

I just wanted to let you know I had several interesting conversations with people this week because of your newsletter